In this series of blog posts, we will take you through the creative process behind Kinesics. This artistic research project explores the future role of body language in Virtual Reality. This is the seventh post in a series of ten.

With our next prototype, Switched Hands, we wanted to create an embodied situation that can only happen in VR. Instead of replicating a game that can be played in real life, like we did with Charades, we wanted to push this feeling of embodiment out of the realm of the possible, to see where it breaks. How far can we go before you don’t feel in control of your online body anymore? We started experimenting with bigger limbs, scale changes, invisible limbs etc. The most interesting idea was the possibility of controlling each other's limbs in VR. So instead of controlling your own arms, you are actually moving the other person’s, and that person is moving yours.

Before we put any time and effort into programming this functionality, we tested it out by simply sharing or switching the controllers. Simple activities like playing catch or navigation became confusing, but also really fun! You need a certain sense of communication and cooperative flow to get anything done.

As an experiment this was a success. But, in order for it to be a prototype that we could share with other people, we needed to give a player something to do. What activities would be interesting to do when you control each other’s hands? What kind of play could we facilitate?

This led to our second prototype: - Switched Hands. Here, we wanted the player to be led through a maze by interpreting pointers from their own hands, which were controlled by the other player. We would build in various puzzles that would allow for creative and expressive hand gesturing.

We premiered and playtested this prototype at IndigoX in Utrecht, June 2019.

Decisions made

Firstly, we tried an asymmetric set-up. One player was guiding the other and could oversee the maze. The other player followed the instructions to navigate the maze, including solving puzzles to unlock doors. This setup felt very constrained as both players were only offered a limited challenge and each had a very set role in communication. One player was telling the other player what to do, and the maze runner just needed to execute it. This set-up was very linear and lacked space for expression - it didn’t feel right.

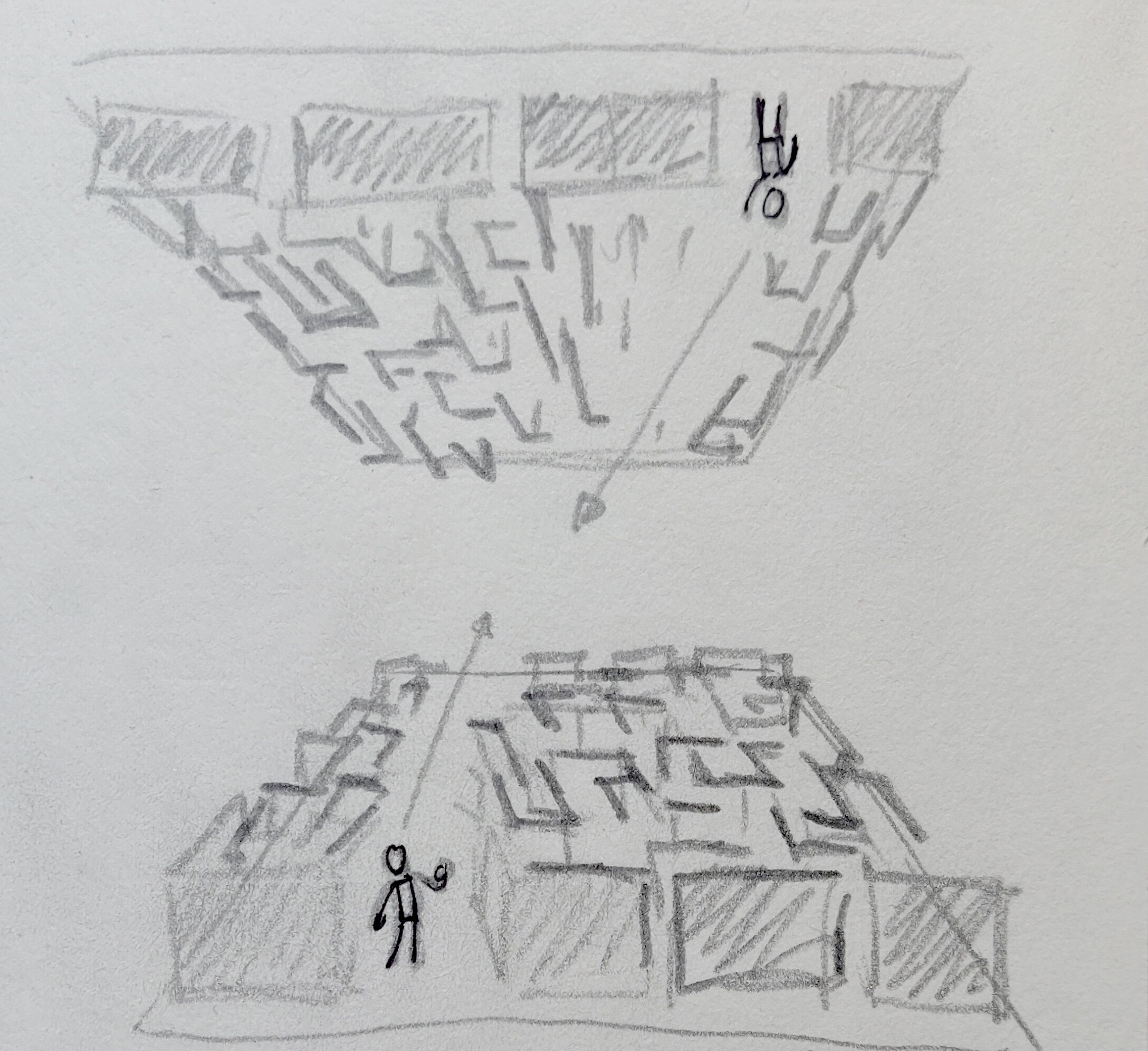

Secondly, we changed the setup so both players had the same challenge. We put both players in two separate mazes. Each maze gives you a clear view of the other players maze, enabling you to help them and vice versa. Each maze had a number of locked doors which a player could open by entering a three symbol code. Player one’s own code was hidden from them, but was visible for player two. Players were encouraged to find a way to communicate the right code without using their voice. The players got no instructions on this, they needed to figure it out themselves by looking at the hands in front of them, and at the player avatar on the ceiling.

Lesson learnt

The biggest challenge was making people look in the right direction. Sometimes, players were looking up at the other, while they should have be looking at their hands, because the other player was trying to tell them something. Because of the huge limitations in communication, it wasn’t clear for both players what the other was doing. This resulted in a mess of both players gesturing at the same time, or both waiting for the other to do something. We patched this up with a squeaky toy to grab the other players attention, but ultimately this was a bandaid on a far too opaque system of communication.

Lessons learnt

In the first minutes of the game, players were negotiating a protocol for communication, and establishing their own grammar. Every couple did this in their own manner. Some solved all the codes for the other first, others changed roles after every code was solved. Some players acted out the symbols, others gestured to the right symbol. The players that invested in creating a joint language at the beginning had a lot of fun, the players that didn’t experienced a more confusing playthrough.

Lessons learnt

During playtesting with children, we saw that some of them liked the lobby of the game more than the actual game! The lobby was just this empty room where you wait together until you are both ready to start the game. We saw a lot of emergent play happen between players in this empty room. Then, when they started the game, they were both put in their own maze, and were separated from the biggest driver of play; each other. We saw attention dwindle quickly.

Lessons learnt

Switched Hands was quite a challenge to play. Players needed time to get familiar with this new embodied situation of controlling someone else’s arms, and even more time to create a joint language and flow together. Only a few teams opened all five doors and got to the end of the maze. The initial period of negotiating a common language and protocol was challenging and often frustrating. But, people still found it interesting to be presented with this challenge on communication, and many did solve at least one or two locks.

Lessons learnt

We realised that this prototype did not match our initial ideas. We wanted to design a game about the interpretation of body language. Yet, the game design had too many restrictions or rules to facilitate body language, self expression and emergent play. Another error in our design was the big separation between players. We realised that we should have placed the players closer together to support communication between them.

Decisions made

In the end, Switched Hands led to a spin-off project within ImproVive called Anamika. This is a two-player-project with two players in VR controlling a four armed goddess.

In our next post we’ll talk about our the design of the third prototype ‘Ghost Hands’. This research was a collaboration with ImproVive and funded by Creative Industries NL.